In the programmatic ecosystem, ads.txt tackles one of the most persistent and costly problems: ad fraud. Fraudsters siphon billions of dollars every year by selling fake inventory, misrepresenting domains, or inserting themselves into supply chains where they absolutely don’t belong. For publishers, this means lost revenue, diluted reach, and a bidding environment where legitimate impressions compete with counterfeits.

Ads.txt takes a refreshingly simple approach to this complex problem. As a publicly accessible text file placed at the root of your domain, it allows buyers to verify whether a platform is genuinely authorized to sell your inventory. For anyone running programmatic ads — including WordPress publishers using AdSense, ad networks, or SSPs — providing an ads.txt is recommended for stable monetization.

This guide offers a comprehensive walkthrough of what ads.txt is, how it originated, and why publishers benefit from keeping it clean, complete, and up to date.

At its core, ads.txt is an industry standard that lets publishers publicly declare which companies are officially authorized to sell their digital ad inventory. The acronym stands for Authorized Digital Sellers, and the purpose is straightforward: bring transparency to the programmatic supply chain by publishing a verified list of trusted sellers.

The IAB Tech Lab developed and maintains the ads.txt standard as the central technical specification for programmatic advertising. Thanks to broad industry support, ads.txt has become one of the most widely adopted tools for reducing fraud and improving supply-chain visibility that DSPs, SSPs, exchanges, and publishers rely on to maintain trust.

Ads.txt emerged as a response to real threats: domain spoofing and falsified reach. Before its introduction, fraudsters could claim to sell inventory from premium publishers while delivering ads on low-quality or fabricated sites. Advertisers often bought spoofed inventory unknowingly.

The IAB Tech Lab released ads.txt in 2017, and it has since evolved to include app-ads.txt, extending the same principles to mobile apps and OTT environments. Over time, ads.txt became embedded in programmatic buying logic — DSPs now routinely check it to validate authorized sellers before bidding.

Ads.txt sits alongside two other essential transparency initiatives: sellers.json and the SupplyChain object (schain). While all three address similar challenges, each plays a different role in the verification process.

Together, these tools form a multi-layered transparency framework: domain-level authorization, platform-level disclosure, and impression-level verification. For buyers, this provides a much clearer picture of how inventory flows through the ecosystem. For publishers, it adds structural protection against misrepresentation.

Domain spoofing is one of the most damaging forms of ad fraud. Here, bad actors misrepresent their inventory as belonging to high-quality domains — even though they serve the actual impression elsewhere. Without a mechanism to validate seller identities, buyers frequently overpay for inventory that does not meet brand safety, quality, or reach expectations.

Ads.txt allows DSPs to cross-reference sellers against a trusted, publisher-owned source. If a seller is not listed, buyers can automatically avoid bidding, eliminating a large portion of spoofed inventory.

Another widespread issue is the uncontrolled resale of inventory within opaque arbitrage networks. A single impression may pass through multiple intermediaries, each adding margin without adding value. This ad flow creates inefficiency, disrupts pricing, and complicates reporting.

Because ads.txt requires publishers to explicitly declare DIRECT vs RESELLER relationships, buyers can differentiate between first-party and third-party routes. This transparency helps advertisers filter out excessively long or undesirable paths, and encourages cleaner supply chains overall.

Publishers who maintain a complete and accurate ads.txt file gain several significant benefits:

Marketers also benefit significantly from the widespread adoption of ads.txt:

For advertisers, ads.txt translates into cleaner media plans and more dependable campaign outcomes, which ultimately benefits publishers as well.

For ads.txt to function reliably at scale, the standard must define strict rules governing the file's location, structure, and long-term maintenance. These technical requirements ensure that crawlers can automatically discover the file, interpret its contents correctly, and align its signals with the rest of the programmatic ecosystem.

The ads.txt file must always reside on a website’s root domain. This placement is non-negotiable. Buyers expect to find it at predictable paths such as: example.com/ads.txt

From there, crawlers extract the list of authorized sellers and match them against bid requests.

Although subdomains host their own ads.txt files, the root domain must reference them explicitly in its ads.txt. Without this reference, crawlers may ignore subdomain files entirely or fail to connect them to the main domain’s inventory. The logic is simple: the root file acts as the central directory; subdomain files are extensions that must be declared.

Verifying whether an ads.txt file exists and is publicly reachable is surprisingly straightforward. You can append /ads.txt to your domain name in a browser. If the file loads cleanly, that’s a good first signal that redirects, firewall rules, or incorrect permissions don’t block it.

Typical red flags include:

Because buyers rely on automated parsing, even minor syntax errors can lead to blocked bids or lost revenue.

A valid ads.txt file uses a consistent, predictable format that represents each authorized seller—whether an SSP, an exchange, or a reseller—with a single line. That line contains three mandatory fields and one optional certification field. Together, they enable ad platforms to verify who is authorized to sell your inventory.

Here is what each field represents.

The canonical domain of the platform you are working with. This entry identifies the ad system that is permitted to sell your impressions.

This unique ID identifies your account within that system. You can view it as your account identifier in the exchange’s backend.

Either DIRECT (you, as the publisher, have a direct agreement with the platform) or RESELLER (an intermediary is selling your inventory on your behalf).

Used for programs such as TAG, providing an extra layer of validation for buyers.

A standard entry might look like this:

exampleexchange.com, 12345, DIRECT, f08c47fec0942fa0The domain names the platform, the numeric ID identifies your seller account, DIRECT describes your contractual setup, and the final value is an optional TAG certification.

With version 1.1 of the ads.txt specification, the IAB Tech Lab expanded the format through Variable Declaration Records. These allow you to attach relevant metadata directly inside the file and can be extremely helpful when operating multiple domains, subdomains, or complex ad setups.

Two common variable types are:

An email address, phone number, or URL for operational communication. This information is beneficial for SSPs or demand partners that need to contact your AdOps team.

A declaration that a specific subdomain maintains its own ads.txt file. Crawlers should check subdomains independently rather than relying solely on the main domain.

Some tools also support additional structured variables, such as inventorypartnerdomain or more specific CONTACT fields, as long as they comply with IAB conventions.

A combined example might look like this:

exampleexchange.com, 12345, DIRECT, f08c47fec0942fa0

CONTACT: adsops@examplepublisher.com

SUBDOMAIN: news.examplepublisher.comThe first line is the core authorization. The CONTACT line provides a direct communication channel for operational queries, while SUBDOMAIN instructs crawlers to fetch and validate the ads.txt file at news.examplepublisher.com. This setup is particularly valuable for publishers with multi-section websites, sub-brands, or separate ad stacks across different site areas.

At its core, ads.txt is deliberately simple: a plain text file, free of formatting tricks or markup. That simplicity is exactly what makes it reliable — crawlers can read it easily, and the ecosystem stays predictable. You can create or update the file using your hosting provider’s file editor, an FTP client, or a plugin like AdPresso that generates it dynamically, and place it directly in the webroot.

The choice of tool matters less than the process behind it. A solid workflow ensures you can quickly add new partners, remove deprecated or inactive accounts, consistently reflect changes to subdomains or site structure, and maintain a syntactically correct file. Neglecting ads.txt can damage revenue as much as not having one, leading to blocked bids, lost revenue, and frustrated AdOps teams.

Modern publishing setups are often more complex than a simple homepage. Multiple properties, redirects, or multi-site environments can complicate your ads.txt strategy. With a few clear rules, though, even sprawling architectures stay manageable.

If you operate multiple subdomains — for example, blog.example.com or shop.example.com — and each uses its own monetization partners, each subdomain requires its own ads.txt file. Otherwise, crawlers receive conflicting signals about which IDs are legitimate.

Your root domain should include declarations such as:

SUBDOMAIN: blog.example.com

This entry indicates to crawlers that they should also fetch:

blog.example.com/ads.txt

A key rule: ads.txt cannot contain redirects.

If a referenced URL triggers a redirect, most crawlers simply ignore it. In multi-site WP setups or larger domain portfolios, keep the paths direct, static, and clearly declared.

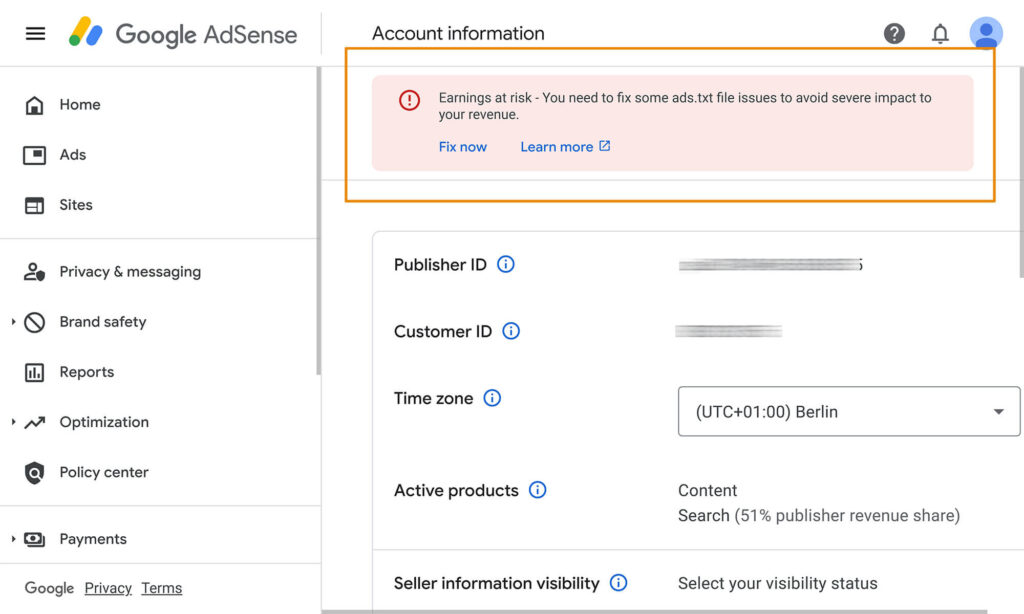

Google AdSense is particularly strict about ads.txt compliance. The system displays warnings such as "Earnings at risk" or "Unauthorized seller" when the root file is absent, the publisher ID is incorrect or incomplete, subdomains lack a declaration, or redirects or permission issues block crawler access.

Until you fix these issues, AdSense may limit or even suppress monetization. The fix is usually straightforward: log in to AdSense, copy the publisher line, add it to a properly formatted ads.txt file at the root, and ensure any subdomains are declared. Status updates typically propagate within 24–48 hours, restoring expected ad delivery.

Large ecosystems — such as AdSense for Platforms (AFP), marketplaces, or user-generated-content networks — operate at a different scale. They often manage thousands of sub-accounts, and in this context, the Public Suffix List (PSL) becomes relevant.

Domains such as co.uk cannot host an ads.txt at the absolute top level, so verification relies on each subdomain acting as its own authority.

In AFP environments, the data-ad-host attribute embedded in the ad tag helps maintain clarity. Rather than listing countless individual sub-accounts in a single ads.txt file, publishers can authorize a higher-level host ID that covers the broader structure.

This approach offers:

For marketplaces or platforms with distributed publishing environments, this is what makes ads.txt maintainable without drowning in complexity.

Integrating ads.txt is a key step toward improving transparency and security in programmatic advertising. At its core, there are two main approaches to implement the file on your website.

The manual method requires creating the ads.txt file in a plain-text editor. You must add all authorized sellers with the correct syntax, then upload the file via FTP or the hosting panel to the website's root directory, ensuring it is accessible at a path like example.com/ads.txt.

This approach gives you complete control, but it requires technical knowledge and ongoing maintenance to avoid errors and keep the file up to date.

For site owners looking to manage ads efficiently, plugins like AdPresso can automate the process. These tools detect your existing partnerships, generate correctly formatted ads.txt files, and intelligently merge any pre-existing files without creating duplicates.

Ad plugins simplify maintenance, minimize error-prone steps, and ensure your file aligns with the current market landscape.

Both methods are valid—manual works best for small, technically savvy publishers, while automated plugins are more efficient for larger sites or networks. The key is consistent upkeep: a well-maintained ads.txt maximizes both protection and revenue potential.

Mobile apps need a version of ads.txt too — enter app-ads.txt, the “little sibling” of the web-based standard. Apps don’t live on fixed domains; they exist in stores like Google Play or the Apple App Store. Fraudsters can exploit this by creating fake copies and selling inventory under false identities. App-ads.txt solves the problem by linking authorization to the app’s store metadata rather than a domain.

Developers register their website URL in the store profile — essentially a digital signpost. DSPs and SSPs append /app-ads.txt, retrieve the file, and verify authorized sellers in the same format as standard ads.txt. Developers with multiple apps can use subpaths. Only bids from listed sellers are accepted, creating a protective layer against SDK spoofing and “Appnapping.”

App publishers see clear benefits because the standard blocks unauthorized resellers, prioritizes genuine inventory, and secures revenue. Store-based attribution ensures stable demand from brand budgets, driving higher CPMs and overall earnings. Publishers also build credibility, signaling that their inventory is trustworthy and less susceptible to fraud.

Since its 2017 launch, ads.txt has become a programmatic industry standard, largely thanks to strict adoption requirements from major networks like Google. Today, over 60% of top publishers use the standard, significantly reducing domain spoofing, while networks like DoubleClick and AdSense continue to apply pressure by filtering unauthorized inventory.

Initially, coverage was slow—only 8–20% of top sites used ads.txt—but adoption surged in 2018 after Google announced it would filter unauthorized inventory from auctions. Key players like OpenX and other SSPs accelerated adoption, and now roughly 45–60% of relevant domains have implemented ads.txt—a major milestone for transparency in programmatic.

Short, focused ads.txt files are incredibly valuable. Lists with hundreds of entries are often partially ignored by DSPs, leading to blocked bids and reduced revenue. Too many RESELLER entries can also invite unnecessary arbitrage. Lean files enable faster crawling and discourage fraud bots that exploit excessively long lists.

Bot caching can delay changes by several days, so allow 24–48 hours after updates and verify with tools like Google Search Console or adstxt.guru. Common pitfalls include syntax errors (wrong commas or tabs), caching plugins (e.g., WP-Rocket), blocked user agents, or incorrect MIME types. The fix is usually simple: upload the plain-text file with the text/plain MIME type, bypass caching plugins, and keep backups before major updates.

Ads.txt effectively combats domain spoofing and unauthorized sellers, but it does not prevent click fraud, invalid traffic, or bot impressions—real user engagement remains unverified. It’s not a silver bullet but a foundational piece alongside sellers.json and SupplyChain objects. Publishers need monitoring and clean practices to reap full benefits.

Ads.txt has firmly established itself as an indispensable standard. It protects against domain spoofing, arbitrage, and unauthorized sellers while providing a simple, lightweight technical solution. From root placement to standard entries and app-ads.txt for mobile apps, it brings clarity to complex supply chains and strengthens trust in digital inventory.

Even with limitations like no built-in protection against click fraud or invalid traffic, ads.txt remains a milestone. Coupled with sellers.json and SupplyChain objects, it creates more stable revenue streams for publishers and safer media for buyers — a true win-win. Long-term, diligent maintenance, whether manual or via plugins like AdPresso, pays off by securing market position and revenue. As the ecosystem evolves, new standards such as llms.txt may appear, but ads.txt will remain the cornerstone of transparent, fair programmatic advertising.

An ads.txt file is a simple text file located on the root domain of a publisher's website (e.g.,example.com/ads.txt). It lists all authorized sellers and their account IDs, serving as a public record to prevent ad fraud like domain spoofing and bring transparency to the supply chain.

Yes, ads.txt is essential for Google AdSense. If you miss the file or if it contains an incorrect Publisher ID (e.g., pub-123456789), AdSense will display the warning "Earnings at risk," and you risk losing up to 100% of your earnings. AdSense crawlers strictly check the file. Therefore, correct implementation is a prerequisite for ad serving and full monetization.

Using a text editor, enter authorized partners in the format: "domain.com, accountid, DIRECT/RESELLER, tagid." Upload it as "ads.txt" to the root directory using FTP or your hosting panel. Plugins like AdPresso can automatically generate this file from your existing partnerships. After uploading, check the file via your browser at example.com/ads.txt and wait 24–48 hours for crawlers to update.

Large networks like Google AdSense block earnings ("Earnings at risk"), DSPs filter out bids, and your revenue decreases by up to 100%. Unauthorized sources are ignored, thereby disadvantaging legitimate publishers and favoring fraudsters. It is mandatory for transparency in programmatic advertising—without it, you lose market share and trust.

DIRECT signifies a direct contractual relationship between the publisher and the platform (highest priority). RESELLER indicates a reseller authorized by the publisher who acts secondarily (carrying a higher arbitrage risk). Clear labeling allows buyers to control chain lengths and filter undesirable paths for supply chain transparency.

App-ads.txt is the mobile equivalent for apps that lack a domain. Developers link their website within app store metadata. Crawlers download developer.com/app-ads.txt using the same format. This standard protects against appnapping and SDK spoofing, increasing revenue through verified sources. It became an IAB standard in 2018 and is particularly relevant for Android/iOS publishers.